“There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot.”

With these words, Aldo Leopold, the noted 20th century conservationist, threw down the gauntlet. In his book, A Sand County Almanac and Essays from Round River, he challenged a modern, consumer society to place value on things that have no value—on things that are wild, natural and free. As the father of wildlife management, he was especially interested in animals and the places they make their homes—their habitats.

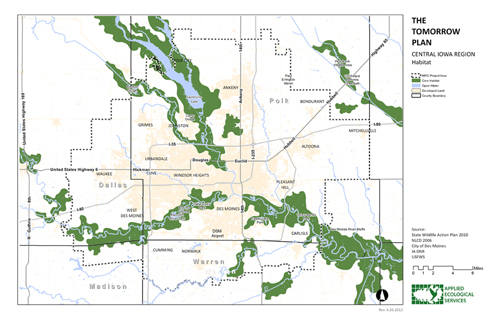

What does this have to do with regional decision-making and The Tomorrow Plan? Lots. For one, things that are wild, natural, and free are a scarce commodity. Iowa is notable among the fifty United States in having the least wild land left. What is rare, like gold or a painting by Leonardo da Vinci, ought to be valuable. The Tomorrow Plan presents a chance to put value on wild things by figuring out how to accommodate and even restore them, despite future growth. Second, perhaps a quarter to a third of Iowa’s species are in trouble. These species aren’t officially endangered, like the prairie fringed orchid or Indiana bat. Rather, they have been in decline for decades simply because of how we use land. Strategies to restore diminishing wildlife are laid out in Iowa’s Wildlife Action Plan. One sure-fire strategy is to give wildlife places to raise families—what wildlife needs most are large reserves and high quality habitat. The map shows where some of these areas are in the region.

Core habitats are green, white areas are agricultural, and pale yellow areas are developed.

The third link between wild things and The Tomorrow Plan is simply this: choices made today about wild nature will be witnessed by generations yet unborn. Sustainability is all about making choices so that future generations are not harmed. For many people, harm includes the extinction of species.

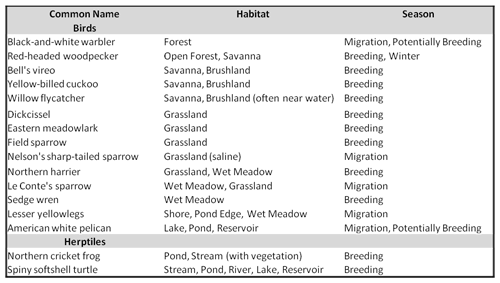

The good news is that nature is resilient. Given enough space, the whistle of Upland Plovers and booming of Prairie Chickens could be heard again in central Iowa. With big enough forests, Barred Owls and Red-shouldered Hawks will hunt here for hundreds of years. If room is made to enlarge wetlands, children in grade school in the year 2050 could see the mating dance of Sandhill Cranes and try to catch Softshell Turtles in the region’s clear-running waters. Below are some species whose presence indicates a region is ecologically healthy.

The Tomorrow Plan is about making choices. It asks us to pause, consider, and decide. No one wants to drive a species extinct, yet without knowing, we have repeatedly done just that. For species not yet endangered but struggling, we can decide to keep them around. Across the nation are projects that amply show how the process of development not only accommodates but restores wild nature. What is not proven is that you must choose between wild, natural, and free things, or meeting the needs of people. That either-or question simply should not be asked. Instead, in The Tomorrow Plan, we are deciding if we should make room for wild nature and wildlife in the region. Wanting to be good stewards of the land, we should also want to keep and nurture what we have without taking anything away from the future—not just prosperity, but also wild and natural things.

Kim Chapman is an ecologist with national experience in ecological research, ecosystem restoration and management. He brings ecology and science to regional, municipal and site-level design and planning projects. He is a principal ecologist with Applied Ecological Services and the lead scientist for The Tomorrow Plan.

Kim Chapman is an ecologist with national experience in ecological research, ecosystem restoration and management. He brings ecology and science to regional, municipal and site-level design and planning projects. He is a principal ecologist with Applied Ecological Services and the lead scientist for The Tomorrow Plan.