Are we afraid of the future? For sure, the economy’s got us all worried. But I’m talking about being just a little nervous about what’s going on with the weather. How much snow is going to fall this winter and what will happen when it melts? Will it be a wet spring? I know readers are a step ahead of me and thinking…flood [1]. This is what I mean when I wonder, are we afraid of the future, because we don’t know what’s going to happen and we can’t control it?

I learned recently that the cost of Iowa’s 2008 flood was 8-10 billion dollars[2]. Put this in perspective:Iowa’s gross domestic product was 135 billion dollars in 2008, so the floods cost about 6-8 percent of Iowa’s annual economic output. Maybe that’s not such a big deal and we can absorb it every couple of years. On the other hand, it is a huge deal to people who endured the floods. Maybe together we can absorb the economic costs, but what individual wants to deal with the emotional ones?

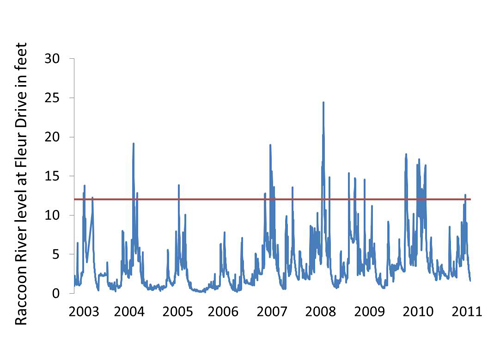

Red line represents flood level.

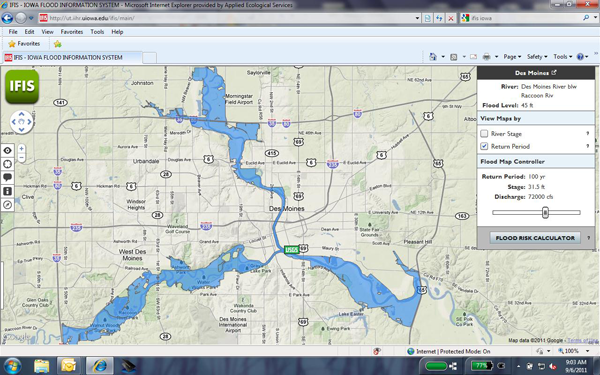

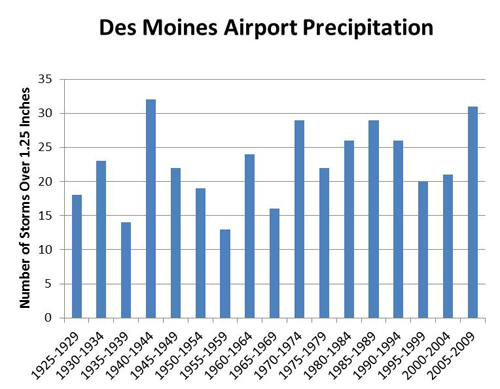

The Army Corps of Engineers[3] and Dr. Eugene Takle[4] of Iowa State have told us that big floods are happening a little more often, more rain is falling, and more of that rain comes in bigger storms. You can see that in monthly precipitation data from the Des Moines Airport and in water level data from the Raccoon River. But as an ecologist, I wonder more about how the condition of the land affects flooding than the problem of more rain. Quoting Charles Ellet, an engineer who studied this question for the Mississippi in the 1850s: “The water is supplied by nature, but its height is increased by man.”

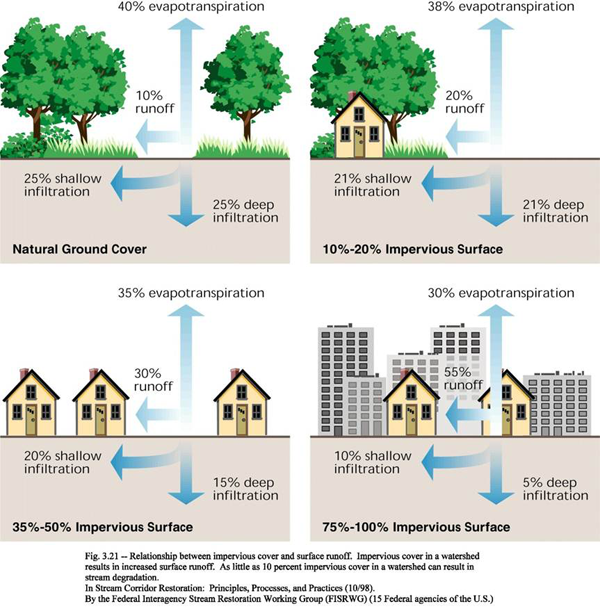

What does that mean? Ellet was talking about levees raising the river level, but he could have been talking about how much more rain runs off streets, rooftops, and tiled cropland than off land in a natural state, as illustrated in this figure.

For city people, the issue is connected impervious cover (CIC)—a big phrase for a simple idea—rain falls on a rooftop, flows through gutters and pipes to a parking lot, which drains to the street and a storm sewer inlet, then falls directly out of a storm sewer outlet into a creek or river. The flow path from where a raindrop lands to where it ends up is all connected. Once you hit 10% CIC, you can expect your stream to start changing. Get to 20% CIC, and the stream shifts to a new condition—eroding bed and banks, lots of sediment, and a simpler community of fish and aquatic insects[5].

Everybody complains about the weather, but nobody does anything about it. It’s driven by what happens ten thousand miles away, making it hard to see what can be done locally. I can accept that—but what about the condition of the land? Ecologists complain about it, but people can do something about it. For any situation, there’s an answer, and it’s written down in any number of books, scientific publications and the like. There’s a whole Iowa manual on how to build streets, houses, and towns without turning up the volume on runoff[6]. The Tomorrow Plan will build on these ideas and also find new strategies to turn ideas into action.

It’s as if we’ve got two handles controlling how much water is pouring out of the faucet—one is rainfall, and it’s slowly ratcheting up. The other is land cover, condition or use, and we can increase or decrease the flow off the land, depending on which way we turn the handle.

This gets me thinking about another topic: who pays? Should communities lower down in the watershed pay to repair a trail that’s falling into their creek? Or should communities uphill who have turned up the runoff volume through needed development pay to make the repairs? What about farmers who put underground drains (“tiles”) in cropland to maintain good yields—which only makes sense for their families and crops. Should they pay for the extra water hurting people downstream? Or should people downstream pay the farmer to hold back or clean up water, as is being done in some places[7]?

For the answer, tune in a few years from now when this conversation reaches maturity. For now please ponder this: rather than just let the environment happen to us, we can do things to land cover that cushions the blow—and that will let us worry a little less about the future as far as the weather goes. As for the economy…well, that’s a different kettle of fish.

For more, read A Watershed Year: Anatomy of the Iowa Floods of 2008 edited by Cornelia Mutel.

[1] Iowa Flood Information System http://ut.iihr.uiowa.edu/ifis/main

[2] http://www.rio.iowa.gov/resources/reports/2011.04_RIO_Quarterly_Report.pdf

[3] http://www.mvr.usace.army.mil/PublicAffairsOffice/DMRRFFS/DMRRFFS-FinalReport.pdf

[4] http://climate.engineering.iastate.edu/Document/Climate_Changes_for_Iowa_12.pdf

[5] Center for Watershed Protection http://clear.uconn.edu/projects/tmdl/library/papers/Schueler_2003.pdf

[6] http://www.intrans.iastate.edu/pubs/stormwater/index.cfm

[7] http://www.ctic.purdue.edu/resourcedisplay/337 and http://www.ctic.purdue.edu/resourcedisplay/365

Kim Chapman is an ecologist with national experience in ecological research, ecosystem restoration and management. He brings ecology and science to regional, municipal and site-level design and planning projects. He is a principal ecologist with Applied Ecological Services and the lead scientist for The Tomorrow Plan.

Kim Chapman is an ecologist with national experience in ecological research, ecosystem restoration and management. He brings ecology and science to regional, municipal and site-level design and planning projects. He is a principal ecologist with Applied Ecological Services and the lead scientist for The Tomorrow Plan.

Thanks for this informative article. I want to see people in our Metro area figuring out answers to the question “Who pays?” as well as considering the main question before us as we plan, What do we need to do starting now to avoid increasingly costly damage in the future? I have observed first-hand for the last ten years the increasing damage flooding has done to the green-belt trails along Walnut Creek in Urbandale and Des Moines. It shows up not just in the trail surfaces needing frequent repair but in destruction of the trees and other creek-side vegetation. As the vegetation is damaged, it absorbs less water and the problem keeps worsening. So many beautiful trees we enjoyed for years have now fallen into the creek. In many places once beautiful creek banks where wildflowers bloomed are now covered with rocks or broken up concrete pieces, in an attempt to slow down future erosion.

In Iowa, around 86 percent of land is in agricultural production, which makes farm owners and operators key players in flood prevention. Similar to urban planners/decision makers, farmers must be stewards of the land. Iowa’s very precious, very dark, rich soil was formed and protected from erosion by deep, dense roots of prairie grasses that covered our land before industrial agriculture transformed our landscape. But we don’t have to turn back the clock or recreate the past to care for our land–to slow soil erosion and reduce flooding. Just as we can require that city developers do not build in flood plains, we can require that all farm owners and operators utilize known soil conservation practices, like buffer strips and grass waterways, and refrain from planting up to the waters edge. Every Iowan should read the report or watch the video, “Losing Ground” at http://www.ewg.org/losingground. These practices protect water quality and slow loss of our precious agricultural soils. The practices are subsidized by federal programs, but when the price of corn and soybeans rise, many farmers abandon these practices in order to clear a higher profit.

One possible way the public could partner with farm owners and operators in flood prevention would be to share the cost (via a state-funded program) of preserving strips of land along water ways as public parks or public hunting areas.

Margaret and Lynn, I appreciate your thoughtful comments. Yes, I’ve heard about and seen the changes in the region’s streams…very dramatic and unfortunate. Lynn, you make a wonderful point–just as there are known ways to handle runoff in cities, so there are known ways–and cost-share programs–to handle runoff in rural areas. But as you point out, economics determines whether those practices remain in place long term. It sees to me, then, that the price paid to farmers for those practices isn’t enough to overcome the justifiable impulse of farmers to remove the practices when they no longer make economic sense. In the absence of a legal requirement for farmers to manage their runoff–including holding back more water–the next best thing could be a payment scheme where people downstream pay people upstream to hold back and clean water. Of course, this may stick in the craw of folks who believe that there is a basic level of pollution that everybody is entitled to create (we all burn fuel to heat out homes, run our cars, etc.), but that there is also a limit to how much someone should be allowed to pollute–because it causes an unreasonable amount of harm to somebody else–think of laws that don’t allow direct discharge of raw sewage into streams. That level of pollution is something that society as a whole thinks a person or institution shouldn’t be entitled to.